How to Prevent Knee Pain as a Dancer

I bend without breaking and wear a cap instead of a crown, knock when nervous and allow you to sit down. What am I? Your knees!

This December we’re focusing on knee needs. From strengthening to stabilising, everyday recovery to injury rehabilitation, we will dive into the caps and creases of knee health and expose harmful myths that may be compromising your training.

Knee Injuries

Injuries in ballet are common yes but they are also preventable. Sadly, over the years the no pain, no gain approach has nurtured the false and destructive philosophy that injuries are part and parcel of the profession and if not inevitable, a matter of misfortune. But it doesn’t have to be like this. The devastating cycle of boom and bust can be managed and even prevented with a structured systematic training regime that addresses common gaps in existing training methods.

But before we dive into knee solutions, let's get to know our knees better.

Knee Mechanics: Muscles, Menisci and Ligaments

The knee joint is the largest joint in the human body and functions to allow the leg to straighten (extend) and bend (flex). Formed by the articulation (joining) of the femur (thighbone), tibia (shin bone) and patella (kneecap), the knee is supported by an intricate web of muscles tendons, ligaments and cartilage including the fibrocartilage pads knows as the menisci. Each tissue plays a unique and crucial role in stabilising the joint.

Ligaments

The knee is supported by four major ligaments: the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL). The ACL and PCL both take their name (cruciate) from the cross shape they form over the front and back of the knee respectively. The ACL prevents the tibia from sliding forwards while the MCL protects the knee from buckling inwards. Due to the high-intensity nature of dancing and the stress placed on the knees during jumps and turns, these ligaments can be vulnerable to sprains and tears if not strengthened appropriately.

Menisci

Other important structures that make up the knees include the menisci. Comprising two C-shaped fibrocartilage rings, the menisci function to increase knee stability by both deepening the socket in which the femur sits and increasing the surface area across which forces are transmitted. Since the medial (near the midline of the body) meniscus is attached to the MCL, damage to the MCL is often indicative of a medial meniscal rupture.

Muscles

There are two main muscle groups that control the movements of the knee: quadriceps and hamstrings. The quadriceps are responsible for extension (straightening the leg) and the hamstrings alongside the gracilis (inner thigh), sartorius (runs down the length of the thigh) and popliteus (small muscle behind the knee) all work to bend the leg. Pain in or around the knee can sometimes be caused by a tightness or weakness in one or more of these muscles.

Knee Pain

Joint pain, particularly knee pain, is not uncommon amongst dancers with injuries ranging from mild tendonitis to ACL tears. This is not to say knee pain or injury is an inevitability, but, as with any elite sport, dancers should be well equipped with the knowledge and resources needed to both prevent and recover from knee pain. Understanding the underlying cause of the pain is crucial to both addressing existing symptoms and preventing reoccurrences.

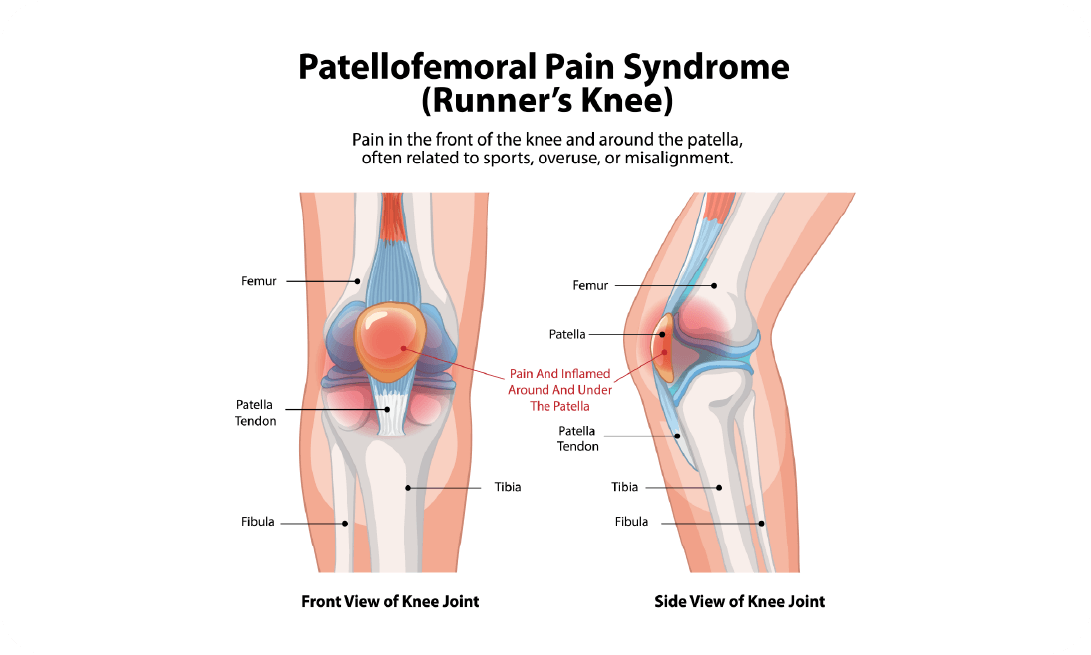

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFP)

In dancers, patellofemoral pain syndrome, aptly renamed, ’dancer’s knee’ is disturbingly common with one study reporting PFP presentations in 49% of female pre and post pubertal dancers. Symptoms of PFP include a dull ache or pain in/around the kneecap that worsens during activities involving bending the knee e.g walking up stairs, squatting or sitting for a long period of time. Dancers are most likely to feel pain during pile’s or when landing from a jump. Tightness or weakness in their inner thighs, quads, hamstrings or hips are thought to be important contributing factors. When suffering from PFP, many dancers report a lack of stability and control in the joint.

Injury Prevention

In an age of TikTok doctors and chatGPT, it is easy to jump to conclusions and self diagnose based on doom scroll findings. Yes, it is true that some injuries are more common than others and tend to affect certain demographics more than others, but this does not mean that other causes should be ruled out nor their accompanying treatment plans. A false or flawed diagnosis, albeit disguised as the answer to your problems, may lengthen the recovery process. There are however simple things that everyone can do to strengthen their joints and improve their knee health. They are the 3 S’s: Strengthen, Stabilise and Stretch.

Busting the Bulk Myth

For far too long, teachers, directors and industry personnel, however unwittingly, have cultivated an unhealthy and frankly unfounded fear surrounding bulky thighs. Indeed, I myself recall being dissuaded from strength training under the guise that I would look more like a rugby player than a ballet dancer if I dared pick up a weight. Horrified at the thought, I abstained from any exercise (other than ballet class) that would have remotely strengthened my quads or hamstrings and only began resistance training in my final three years of ballet school.

The truth is… drum roll please… it takes a lot of protein and a lot of weight training to grow bulky thighs. Even gym fanatics will tell you that gains (increases in muscle mass) are hard to come by if you’re not lifting heavy. Yes, aesthetic and length of line is important but when does it become ok to sacrifice health for looks? The answer is never.

With the ballet core aesthetic back on the rise, leanness and tone is too readily being conflated with thinness. The results: injured dancers, short careers, traumatised artists. If we want to give future generations of dancers the chance to have healthy prosperous careers and meet increasingly demanding choreographic expectations, strength training should not only be considered but prioritised.

Bullet-Proofing your Knees with PBT

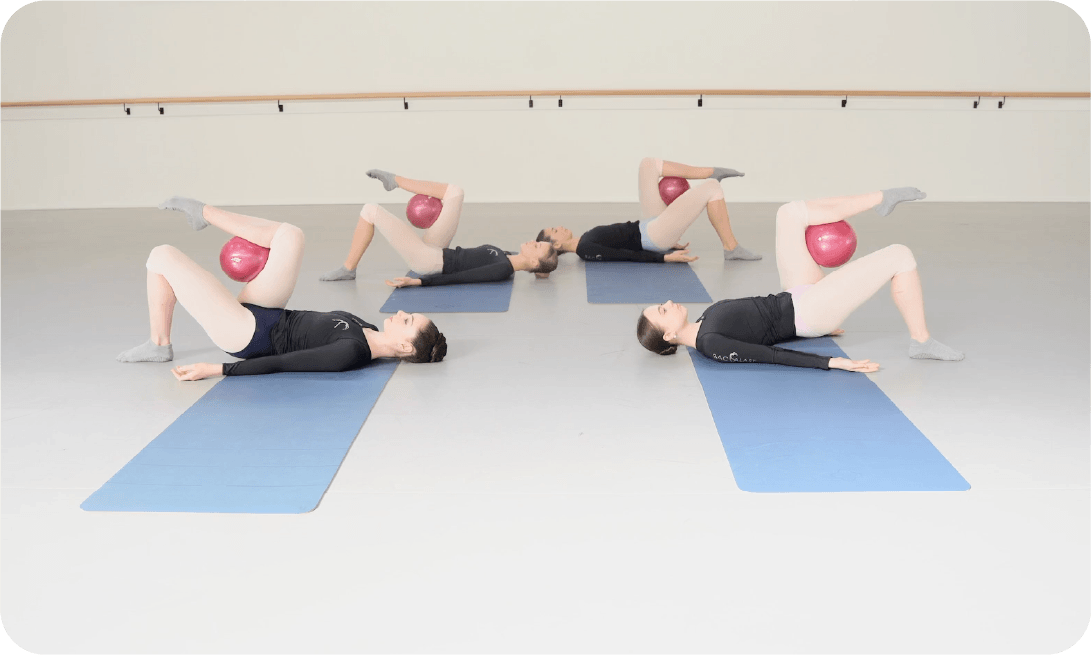

PBT founder Marie Walton-Mahon has dedicated her time to crafting a comprehensive and effective solution to dancer’s needs: Progressing Ballet Technique.

Through a series of expert-led classes, dancers will learn the key principles of knee health including: alignment, stability and strength. In many classes, specialised PBT equipment, providing instant feedback, will help dancers enhance their body awareness and deepen their mind-muscle connection while challenging their core stability. Each exercise is taught, practised and then performed to music to develop the dancers’ coordination and improve their musicality, all the while never losing sight of what dancing is all about: freedom of expression and enjoyment.

December at PBT

Continuing the theme of knee health, this December, we will be sharing tips and tricks on keeping your knees strong for the stage and how to strengthen for hyperextension as a dancer. If you want to learn more about training with hyperextension and why the ballet world seems to be obsessed with abnormally bendy backs and feet, you can read all about it here.

Have a lovely start to Nutcracker season for all those performing and good luck to the many dancers participating in exams, rehearsals and shows this Winter!

By Elise

Sign up to our newsletter

Receive tips, news, and advice.